Mental illness has shaped the work of some of these ‘outsider’ Cuban artists

By: Mimi Whitefield

The Miami Herald

In Cuba’s largest public housing project a 94-year-old man has created a rusty fantasy world from cast-off furniture, office machines, children’s toys and the general detritus of life and transformed these found objects into an eye-popping sculpture garden.

Inside his apartment, every room is jammed with smaller creations fashioned from everything from old plastic telephones and typewriters to animal claws, human teeth, sunglasses and discarded clothing.“These are old, ugly objects, poor objects, of the 21st century.

But nothing is unserviceable just like no one is useless,” says Hector Gallo Portieles, a former revolutionary, barber, journalist, diplomat, and intelligence operative who took up art after retiring and moving to the Alamar neighborhood on the eastern outskirts of Havana in 1990.

“Everything has a new life and is part of the family,” he says of his artistic creations.

On a sixth-floor walkup in the same Alamar neighborhood, Jorge Alberto Hernández Cadi toils in a living room/studio that is stuffed with the materials of his craft: doll parts crammed in a holster, foil blister packs of long-used-up pills, old slides, spurned Russian films, vintage black-and-white photographs and albums that were tossed in the trash.

He turns them into haunting images and installations, often using the old photos and films to supply the heads for the people in his work and stitching crosses and devil’s horns on them with thread. On some, he has cut out the eyes or sewn the lips shut.

Gallo and Hernández, nicknamed El Buzo, are two of at least six Cuban “outsider” artists who live and create in Alamar amidst the crumbling, mildewed buildings of what was supposed to be Cuba’s grand experiment in egalitarian housing. It’s now home to more than 100,000 people.

There are others like them in Cuba and across the globe who haven’t been formally trained in art, who work outside the artistic mainstream and have unconventional world views.

Outsider art, sometimes called Art Brut, had its origins in the collections of 19th-century European psychiatric hospitals where doctors analyzed the work clinically.

Many, but not all outsider artists suffer from mental illness. Social isolation and traumatic experiences inform the works of others.

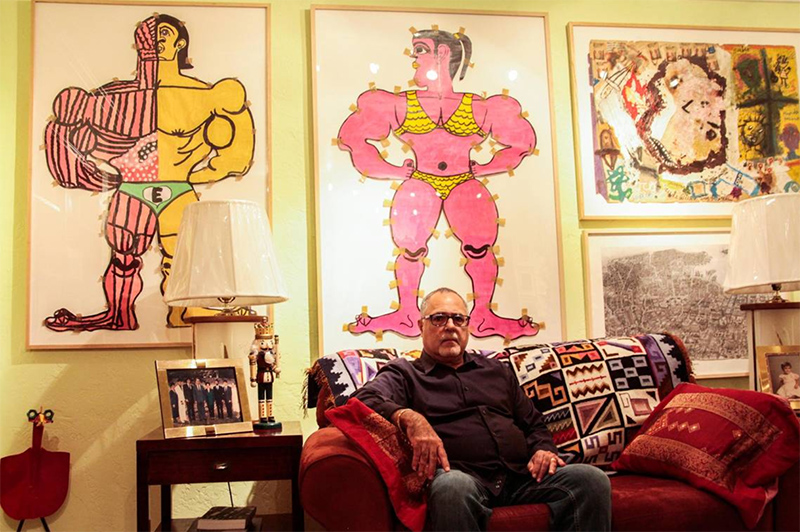

“For me, the outsider artists who live in Alamar are the best,” says Juan Martin, a Hollywood man who is executive director of the National Art Exhibitions of the Mentally Ill (NAEMI). ”I don’t know why there are so many there — maybe because the population is so concentrated.”

The outsider artists are working at a time when the Cuban art world is in flux with a national debate raging over who is an artist and who can sell work commercially. A new Cuban law, which went into effect recently, requires prior government approval for artists who want to present their work in any spaces open to the public, including private homes and businesses. Painters and other artists who commercialize their art without government permission also could be subject to fines.

It remains to be seen how the decree-law will be implemented, but Martin says: “Under Decree-Law 349, they [outsider artists] are not even artists. They haven’t studied art and aren’t associated with any official cultural institutions. They’re not supposed to sell their work.”

Martin, who came to the United States during the Mariel boatlift, has taken a special interest in supporting and bringing the work of outsider artists to a broader audience. His Hollywood home is now filled with more than 1,200 pieces created by outsider artists from around the world. He said he would love to partner with a museum, university or other institution so more people can see his collection.

For years, Martin was a social worker who counseled mentally ill people. One day as therapy, he asked one of the patients to draw a picture. “It was a marvelous work, and it also turned out to be the only work he ever did in his life.”

Martin began to look for such artistic expression among other mental patients. About six years ago, he began to seek outsider art in Cuba and now has about 400 works from island artists.

“The art is not overly commercial. Some people feel threatened by it,” says Martin. But what attracts him is the outsiders’ authenticity. “They don’t care what is in style, nor whether their art can be sold or not,” he says. “Their motivation is just to produce art.”

Gallo says his artwork saved him. He had fallen into depression around the time he moved to Alamar. The former Soviet Union had collapsed and Cuba had entered a bleak “Special Period” when food and fuel and just about everything were hard to come by.

“Now I live in a world of art. For me, this is a world of love and peace,” he says. “At 94, I am totally and absolutely happy. I don’t lack for anything. I am very happy to have discovered my reason for being.’’

The Alamar neighborhood itself is central to the work of both Hernández and Gallo. They have wandered the community in search of other people’s junk to animate their creations.

Hernández earned his nickname, El Buzo (The Diver) because of his habit of scavenging for other people’s castoffs.

As he holds up a boat crafted from paper and filled with small figures cut from black-and-white photos, he explains his work is a riff on migration, separated families and societal conflicts. “Sometimes we’re in one place but spiritually we’re in another place,” he says.

His conversation is lucid, intriguing, but Hernández had an anguished childhood. During a period of depression, he stabbed himself in the chest.

“I had a very fierce situation in my house when I was growing up; it produced a mental disequilibrium,” says Hernández, 55. His work “is inevitably a product” of his troubled childhood.

Using the photos and slides he has picked from people’s trash feels a bit like rescuing lives, Hernández says, adding that he is intrigued by the “hidden history” behind them. “They were in the garbage but once they were a reflection of society, of life.”

Yet another Alamar outsider artist is Misleidys Castillo, who is autistic and mute.

Most of her creations are colorful, cartoon-like depictions of powerful muscle-builder men in tiny tights. She meticulously applies small pieces of brown tape to the outlines of her figures as if anchoring them in place. She generally draws on computer paper that she pieces together for her larger figures.

“We don’t know why she is so attracted to the masculine figures,” says Dr. Lazaro Francisco Mora Pedrosa, her brother. “Sometimes she kisses them and other times, before she falls asleep, she seems to be arguing with them, shaking her finger at them.”

Lately, however, muscular female figures cradling infants have begun to show up in her work.

Mora says his 33-year-old sister has “always painted with agility despite her disability. At times she only wants to paint, not eat or go to sleep. As her brother, I can say I think she realizes something is going on with her art, with people’s reaction to it, but I don’t know what is going on in her interior life.”

Cuba’s outsider artists tend to be unrecognized and unknown by many in their own country. But the work of El Buzo, Gallo and Castillo has been exhibited in private galleries in Cuba and at shows at the Spanish Embassy in Havana.

Now they and other Cuban outsider artists are getting recognition outside the island.

Paris gallerist Daniel Klein brought out a full-color book on Gallo as the first edition in his Art Brut Project and Castillo’s work has been exhibited in Paris and will be shown in Vienna next year.

Hernández and Castillo had a show this past spring at the Frost Art Museum in Miami that was produced in conjunction with NAEMI and Florida International University psychiatry department. Some of the Cuban artists also will be included in an upcoming traveling show of outsider art presented by the Spanish Agency of International Cooperation at its cultural centers throughout Latin America.

Gallo, however, resolutely refuses to sell his work and doesn’t even like to part with his pieces so they can be shown in exhibitions. “It would be like cutting off an arm to get rid of them and sell them,” he says. Asked what his favorite piece is, he exclaims: “All of them!”